LINFOMAS DE BURKITT

En el año 1957 el cirujano irlandés Denis Burkitt vio en Uganda a un niño de 5 años que presentaba tumoraciones en cuello y cabeza y también observó una niña que presentaba las mismas características entonces sospecho que se encontraba ante un nuevo tipo de cáncer que no estaba definido entonces comenzó una investigación y junto datos de hospitales de áfrica y encontró 41 casos que presentaban las mismas características que además en la anatomía patológica se veía el mismo tipo de células en el año 1961 Burkitt dio una conferencia en la cual el virólogo Michael Epstein sospechó que podía haber alguna asociación de algún virus con el desarrollo de esta enfermedad entonces le pidió muestras a Work it para estudiarlas en el año 1963 se bautizó esta enfermedad como linfoma de Burkitt en el año 1964 Michael Epstein e iban Bart publican un trabajo en el que revelan que hallaron partículas virales en las muestras de los cultivos de las muestras que les había enviado Burkitt entonces este virus posteriormente se llamó virus de estimar y fue la primera vez en que se encontró una asociación entre un virus y el desarrollo de un cáncer una pregunta que cree que creen que por esfera en el linfoma de Burkitt células T células de células NK o macrófagos

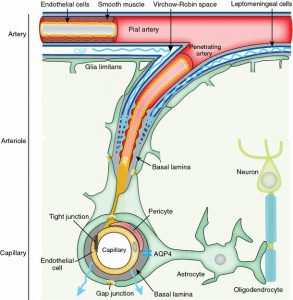

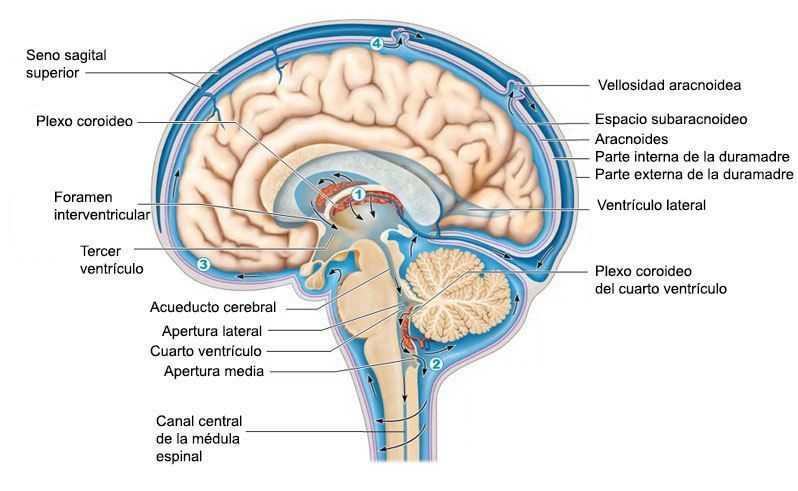

El informe de Burkitt es un tipo de linfoma no-Hodgkin de células ve que es de alto grado es decir que se caracteriza por ser agresivo de crecimiento y diseminación rápidas que se presenta más frecuentemente en niños y en adultos jóvenes cómo se clasifican los linfomas se clasifican en linfomas Hodgkin y no Hodgkin, los no Hodgkin tiene una afectación más frecuente de múltiples ganglios periféricos no se disemina por continuidad tiene una presencia extraño nada habitual en muchos casos leucemia y hay una afectación frecuente del anillo de igual de ayer y ganglios mesentéricos y dentro de los linfomas no-Hodgkin se encuentra el linfoma de Burkitt acá tenemos una un gráfico con la frecuencia no logramos encontrar datos de argentina pero estos corresponden a EE.UU. un 40 por ciento de los linfomas corresponden a linfoma de hodgkin mientras que un 60 por ciento son linfoma no Hodgkin y dentro de éstos los más los más importantes o más frecuentes son el informa difuso a linfocitos b ni forma folicular ni informa de malt informa dispuestos de maduros y solamente un 2.4 por ciento corresponden a linfoma de Burkitt que aproximadamente corresponde a un 66 casos por millón de habitantes la frecuencia en américa del sur es mayor que en EE.UU. y la mayor prevalencia se da en áfrica cómo se clasifica el informa de burkitt se clasifica en endémico esporádico y asociado inmunodeficiencia el endémico se da en áfrica ecuatorial isco y coincide con las áreas en que la malaria es endémica se da un y en los niños con un pico entre los 4 los 10 años de edad con mayor prevalencia en hombres y se ha visto que el 99 por ciento de los pacientes con linfoma de burkitt endémicos son positivos para el virus de steinman o el esporádico se puede dar en cualquier parte del mundo se dan niños y adultos jóvenes también con mayor prevalencia en hombres y tiene una edad media de presentación de 30 años y solamente se asocia en un 30% a virus de bestinver y la sociedad de mono deficiencias principalmente se vean infectados hb y con menos frecuencia en ninguno de suprimidos por trasplante en cuanto a la etiología de la enfermedad tenemos varios factores tenemos factores genéticos predisponentes tenemos virus principalmente el virus Bestinver el htlv 1 y 2 el archivo el virus de estimar en realidad mecanismo no está del todo dilucidado pero lo que genera es una una estimulación antigénica crónica lo cual lleva una estimulación del sistema inmune ésta produce rearreglo de las inmunoglobulinas y aumenta la probabilidad de que se produzca un re arreglo aberrante con la consecuente activación de un protón cogen que más tarde Marianela les va a comentar después tenemos factores ambientales ya sea radiación tóxicos tenemos el estrés y depresión que son factores muy importantes para el desarrollo de esta enfermedad según nos comentaron en el servicio de hematología del hospital todos los pacientes con linfoma o leucemia siempre que se les realiza una anamnesis refieren en los seis meses previos al diagnóstico haber sufrido algún evento muy estresante ya sea divorcio o fracaso laboral muerte de familiares etcétera y tenemos otras enfermedades o comorbilidades o las dejo con mi compañera mariana y la que les va hablar de fisiopatología y diagnóstico bueno vamos a ver un poquito de fisiopatología de la enfermedad lo que ocurre es una proliferación exacerbada de los clones del dispositivo dentro de los centros germinales ubicados en los ganglios linfáticos esto va a llevar a un aumento masivo en la tumoración si no solamente se va a dar en un ganglio específico sino que se puede en múltiples y además tiene alta predilección este linfoma por sistema nervioso central y médula ósea bueno dentro de los linfocitos b y de otras células hay un gen que es el gen mic que es un oncogén que se encuentra en la región 24 del brazo corto del cromosoma 8 este gen codifica para la proteína myc que actúa tanto como factor de transcripción inhibitorio como activador ahora bien este descenso a expresar en alta tasa durante embriogénesis en suelos de tejido con alta capacidad proliferativa mientras que va a ser indetectable en células de diferenciación terminada esta proteína se une como factor de transcripción a un 10 o 15 por ciento del genoma y según a qué parte del genoma se una va a actuar regulando la proliferación la diferenciación la síntesis la apoptosis celular ahora bien qué pasa en el forma de Burkitt bueno el gen mix se atrás loca con la cadena pesada de inmunoglobulina en el 80% de los pacientes mientras que el 20% restante se trastoca con las cadenas livianas capa y landa de estas inmunoglobulinas según el punto de reordenamiento y la ruptura se va a clasificar en clase 1 2 y 3 la clase 1 en la ruptura se va a dar en el primer exxon del gen y la clase 2 cerca de la región 5 prima y la clase 3 un poco más alejada la región 5 pin en la clase unidos va a predominar el informa de burkitt esporádico y asociado y un auto inmunodeficiencia mientras que en la clase 3 va a predominar el endémico ahora bien hay un 10% de los pacientes que si se le hace un fish o una pecera un show de plan no vamos a ver una translocación entre el gel min mic y las cadenas de inmunoglobulina entonces hay hipótesis que se cree que hay alguna desregulación en unos micro líneas que se insertan en el gen o puedo hacer que ocurran mutaciones puntuales dentro del gen mic cualquiera de los dos sea el motivo va a ocurrir una desregulación y una sobreexpresión del mic que lo que va a hacer es en última instancia que ocurra una proliferación exacerbada de estos linfocitos b y además que se detengan en el centro germinal y no puedan proliferar a linfocitos b memorias en las plasmáticas muy bien para ahora voy a comentar la clínica del paciente la clínica el paciente va a depender mucho de donde se aloje la masa tumoral del tamaño y de cuánto se está replicando este linfoma principalmente acá en el informe de burkitt endémico vamos a ver principalmente masas tumorales en la región cervical mayormente también se puede ver la región abdominal se ha visto el mama se ha visto el riñón y muchas veces el prolifera al hueso maxilar y orbital en mi forma de burkitt esporádico se va a ver que mayormente la masa tumoral va a ser a nivel gastrointestinal intestino estómago también se ve algunos casos en la región cervical pero es menos frecuente y también se puede ver en riñón con respecto a la sintomatología inicial va a ser bastante específica el paciente llega a la consulta porque tiene una tumoración en la región cervical sí o sea si lo puede ver no o puede también consultar por vómitos náuseas pérdida de peso en un poco tiempo si el informe se encuentra en la región gastrointestinal sí pero los síntomas los síntomas son bastantes inespecíficos muchas veces como les contó mi compañero estos linfomas tienen alta tasa de proliferación entonces se genera una síndrome un síndrome del issys tumoral espontáneo lo cual va a generar náuseas vómitos en nuestros pacientes que pueden que lleguen y consulten por esto bueno como vamos a hacer el diagnóstico de linfoma de burkitt inicialmente obviamente el médico a ver la clínica el paciente se le va a hacer una tomografía una ecografía se lo hace una función desde ganglio se levantó patológica donde van a hacer una inmunodepresión y biología molecular según la organización mundial de la salud el diagnostico requiere todas estas características clínicas morfológicas inmunes fenotípicas y moleculares ninguna de ellas por sí sola es de goles estándar para poder diagnosticar la enfermedad con respecto a la clínica bueno depende de la variante de tumoral de la localización y el médico para tratar de encasillar la en endémica esporádica o asociado a inmunodeficiencia con respecto a la morfología contención emma toxina cocina se va a ver este es un patrón característico a cielo estrellado donde como el cielo serían todos linfocitos b atípicos que presentan un núcleo con cromatina laxa pueden presentar algunos núcleos el citoplasma va a ser vaso filo y pequeño y las estrellas van a ser macrófagos que tienen en su interior detritos celulares propios de la alta tasa de apoptosis que tiene este este tejido también se le va a ser inmunofenotipificación en el cual vamos a buscar marcadores linfocitos b como son 19 s de 26 79 para 5 y otros y también se va a buscar marcadores de centros germinales y donde yo les conté que se alojan los linfocitos de estos atípicos algunos de ellos 11 de 10 veces de 6 c de 38 6 43 y el kit 67 que es un índice de proliferación acá vemos 11 de ellos positivos utilizar anticuerpos monoclonales específicos dirigidos contraste de 10 vemos un 1567 cercano al 95% y un bcl6 positiva y además el laboratorio cuenta con esto se va a ser una biología molecular para ver la translocación del gen mick con la inmunoglobulina de cadena pesado cadena liviana acá vemos un film en el cual hay una translocación del gel mix con la inmunoglobulina de cadena pesada bien además se le van a realizar otros estudios complementarios al paciente un laboratorio completo hemograma con holograma función renal hepatograma y de serología por lo que contó mi compañera con la asociación que tiene con el virus como el einstein marach y htlv entre otros seguido de esto se le va a ser también una tomografía de pecho abdomen y pelvis para poder descartar cualquier otra masa tumoral no vista hasta el momento y se le va a hacer una biopsia medular y una citología de líquido cefalorraquídeo porque como ya les comenté estos tumores tienen alta predilección por el sistema nervioso central y tenemos que descartar todo esto va a permitir esta edificar la enfermedad del paciente una posible complicación es el síndrome lisis tumoral porque alteraciones se caracteriza no le dijimos pero por ahí lo saben de verlos en sus hospitales muy bien la correcta a la 2 bueno como dije el síndrome dice tu moral es una posible complicación de este linfoma se da principalmente en neoplasias de alta velocidad de crecimiento como la leucemia linfoblástica aguda y linfoma de burkitt y es una una alteración electrolítica que puede acompañarse o no de suficiencia renal aguda se puede dar tanto espontáneamente o secundario la quimioterapia entonces qué va a ocurrir se va a producir un análisis de una gran cantidad de células tumorales con la consecuente liberación del contenido intracelular entonces a partir del adn lo que se va a generar va a ser ácido úrico y se va a liberar potasio y fósforo entonces lo que se va a observar va a ser una hiperuricemia una hiperfosfatemia una hiperpotasemia y una hipocalcemia secundaria la hiperfosfatemia y el paciente la sintomatología que va a presentar como dijo mi compañera va a ser náuseas diarrea vómitos pero la complicación las complicaciones más importantes serían la insuficiencia renal que principalmente se va a deber a la hiperuricemia pero también por la hiperfosfatemia después debido a un aumento del potasio va a ser muy peligroso porque el paciente puede morir por una alteración cardíaca ya sea taquicardia arritmia paro cardíaco y la hipocalcemia lo que va a generar va a

ser convulsiones arritmias entonces es muy importante prevenir este síndrome y lo que se hace es 24 172 horas antes de iniciar el tratamiento quimioterápico lo que se va a hacer es un tratamiento preventivo lo que se va a hacer es una hidratación para aumentar el flujo sanguíneo renal y así aumentar la excreción de ácido úrico y fosfato se va a hacer una alcalinización para que sea que inicie la orina y se aumente la solubilidad del ácido úrico y su excreción y se va a hacer una disminución del ácido úrico ya sea con él o por in all o ralph moore y casa en la locura y nos va a inhibir la santina oxidasa y la repubblica se va a transformar el ácido úrico en alantoína la razón y casa es un medicamento más novedoso pero mucho más costoso presenta muchas ventajas como ser que tiene un inicio de efecto mucho más rápido una vida media más prolongada nos presenta interacciones medicamentosas y no requiere un ajuste de dosis pero la desventaja su elevado costo y me faltó decir que este síndrome se define con al menos dos criterios una creatinina sérica que sea el doble del valor normal para la edad un ácido bórico mayor o igual a 8 un fósforo mayor igual a 5 potasio mayor igual a 6 y un calcio menor igual a 7 en cuanto a tratamiento del informe de burkitt lo que se usa es un esquema

17:37

quimioterápico intensivo que incluye una enorme cantidad de fármacos que existen varios esquemas como el co2 y back lr por el jr hiper edad que siempre se usan en conjunto con el rituximab que es un anticuerpo monoclonal que lo que va a hacer es unirse al cde 20 de los linfocitos b estimulando su muerte por apoptosis y es importante iniciar el tratamiento con rapidez luego del diagnóstico ya que dijimos que es una enfermedad de una velocidad de replicación muy alta en cuanto a nuevas estrategias que están en estudio se está desarrollando en España un fármaco que lo que hace es inhibida al gen mix por medio de inhibidores del bromo dominio extra terminal o beth tenemos a la proteína br de 4 que tiene un bromo dominio por el cual se une al gen mick estimulando su transcripción entonces esto lleva una proliferación de células cancerosas y el fármaco llamado jq 1 lo que hace es inhibir el bromo dominio impidiendo que el verde de 4 se una al gen mic esto va a hacer que se bloquee la transcripción del gen y por lo tanto se impida la proliferación de células cancerosas se basa en un mecanismo epigenético que impide la transcripción de mick se cuenta de etapa preclínica se ha visto que produce un cese una multiplicación celular un comienzo de la diferenciación celular y se ha visto que prolonga la sobrevida de ratones pero presenta desventajas como ser que carece de especificidad porque puede inhibir la expresión de múltiples genes no sólo el ‘mix’ hay otras proteínas lectoras además del bed es decir que el gen mix se puede activar por medio de otras proteínas y por lo tanto es necesario continuar con los estudios en cuanto al pronóstico de la enfermedad es una enfermedad con una alta tasa de mortalidad que tiene una expectativa de sobrevida de 3 a 6 meses y los factores de mal pronóstico son una edad mayor a 60 un nivel elevado de la dh masas tumorales voluminosas y presencia de dos de más de las localizaciones strang y anales de la enfermedad ahora comenzamos con los casos clínicos el caso clínico uno es un paciente masculino de 23 años que consulta el hospital por desmayos astenia disnea palpitaciones catársis negra o melena desde hace un mes presenta dolor y distensión abdominal en cuanto al laboratorio lo llamativo que se encontró fue un hematocrito de 15 con 5 dínamo lobinas de 4.7 y el resto de las funciones renales hepáticas y coágulo gramas encontraban normales presenta como antecedentes gastritis aguda se medica habitualmente economía para sol y niega uso de aines y se establece un diagnóstico presuntivo de síndrome anémico secundario a una hemorragia digestiva alta entonces se realiza una transfusión y una carga de hierro endovenosa con una buena respuesta y se solicita una vida endoscopia digestiva alta en la cual se ve una lesión alterada gástrica de aspecto no proliferativo a la cual se toman biopsias es decir un tumor gástrico se le realiza una tecnología y resulta negativo para él para ti ti sep para hepatitis b hepatitis a y negativo para archivo y es positivo para anticuerpos ige de virus epstein-barr en cuanto a la anatomía patológica lo que se ve es una infiltración difusa por proliferación no plástica constituida por células de gran diámetro de núcleos irregulares núcleo evidente frecuentes en mitosis fenómenos de apoptosis con abundantes este osito que fagocitan restos celulares lo cual es el llamado cielo estrellado que les comento mi compañera se le realiza entonces una marcación y da positivo para hacer de 20s de 10 bcl6 x 67 lo cual es compatible con el informa de burkitt entonces establece el diagnóstico se le realizan dos ciclos de quimioterapia y se le realiza una profilaxis antibiótica con ligo flexas team afro con us olite ms para prevenir posibles infecciones se realiza un primer ciclo 9 de enero y un segundo ciclo del 29 de enero acá tenemos un resumen de los laboratorios que se realizaron durante los tres meses que estuvo internado el paciente acá vemos los valores de ácido úrico de la idea h calcio fósforo potasio y lo que vimos es que no se reúnen dos criterios para definir que haya tenido un síndrome mérici tumoral por lo tanto decimos que se realizó un correcto tratamiento preventivo con alopurinol y lo que vemos es que presentaba unos valores muy elevados del vih lo cual es un factor del mal pronóstico el 18 de febrero se ve en una tomografía una masa tumoral importante con compromiso medias tinal se ve una infiltración pulmonar que lo que hace es llevar una compresión de la vena cava superior el 21 de febrero sufre un traumatismo un traumatismo pulmonar tiene una mala de canicas ventilatoria se descompensa y al día siguiente sufre un paro cardiorrespiratorio y falleció bueno voy a continuar con el último caso el caso clínico 2 un paciente que ingresa más o menos en la misma época que el primer paciente es un masculino 21 años con una consulta en un consultor externo porque ello se ve se nota un tumor en la región cervical derecha y dice que hace dos meses lo tiene y evolucionó creció en crecimiento no tiene ningún otro signo ni síntomas asociados se le realiza una ecografía cervical donde se ve una masa heterogénea de 72 x 32 milímetros predominio sólido de límites mal definidos con importantes actualización asociado a la misma se reconoce en otras imágenes anglo nares de morfología no habitual a partir de esto se decide hacer una punción del ganglio y luego de ésta se le da de alta y les la recomienda que vuelva en una semana para ver si había algún resultado también antes de dar el alta lo que se hace es un laboratorio en los cuales vemos como gran meta grama función renal y holograma y coágulo grama normales

un día antes del turno que tenía programado el paciente vuelve a una consulta por guardia médica donde refiere que hace cinco días tiene fiebre vómitos y se le interna para hacer el diagnóstico y el seguimiento en este momento es un laboratorio donde se ve nuevamente moverán me pato graff función renal ya no grammy coágulo grama normal se le hace una serología donde vemos que el paciente curso con un einstein bar en el pasado y un sito mega lo y active hepatitis b htlv hepatitis as y mono test son negativos a los días de estar el paciente internado llega al resultado anatomía patológica que ya que lo derivamos a la fundación Favaloro porque no contamos con esto en nuestro hospital y se ve este patrón característico que les comenté de si lo estrellado con linfocitos atípicos y los macrófagos con detritos en su interior junto con esto llega la imm una marcación donde se ve que el paciente presenta hasta de 20 positivo si es positivo es el ese dispositivo y un kit en 67 que es un indicador de proliferación 98% todo esto hace que lleguemos al diagnóstico de linfoma de burkitt además este paciente presentó infiltración medular en la primera etapa donde hemos marcado con la flecha estos linfocitos atípicos con cromatina laxas y todo plasma pequeño vaso filo y acá no se ve pero nosotros lo vimos al microscopio que tenía algunos núcleos el día 12 se le hace o sea 12 días después se le hace una toma una tomografía y se ve que el tumor duplicó en tamaño o sea que acabemos la proliferación exacerbada que presentó y se le programan 5 ciclos de quimioterapia bueno vemos que inicialmente se le programa un cóner ecobox y arriba pero después en el segundo ciclo se le da arriba y el paciente empieza a evolucionar bien hasta el tercer ciclo evoluciona bien de hecho en el tercer ciclo éste la Cetrapam o donde se ve que revirtió la infiltración medular o sea entró en remisión a partir de más o menos la mitad del cuarto ciclo el paciente otra vez se le hace una nueva mente y se ve que tenía infiltración del 80% y además que la masa tumoral está nuevamente aumentando o sea que eso nos hace pensar que tiene una resistencia a la quimioterapia acá te mostramos también un laboratorio a lo largo del tiempo donde vemos cómo hacia mi compañera que tiene ácido úrico normal es fósforo magnesio y potasio normal creatinina dentro de los valores por lo cual paciente fue correctamente tratado para prevenir el síndrome del Lisis tumoral el paciente también la quimioterapia va dirigida a médula por porque este linfoma leucemia zona el paciente en el último tramo del tratamiento presenta plaquetopenia intensas por lo cual debe ser politrauma fundido reiteradas veces bueno el 2 de julio el paciente comienza con dos mejoras progresivas aumenta mucho la masa tumoral y de hecho hay una gran infiltración en médula en senos esfenoidales y en las vías aéreas superiores sufre una descompensación además presentaba neutropenia febril producto una clips y la neumonía e bueno unos días después de bolsena con insuficiencia ventilatoria sangrado nunca violar masivo shock hipovolémico y termina muriendo los dos casos fíjense que son pacientes jóvenes fue raro porque fue simultáneo en el tiempo a los dos se los previno el síndrome del issys tumoral con alopurinol el cual respondió bien pero bueno como sabemos y la bibliografía lo remite estos pacientes tienen muy mal pronóstico bueno como conclusiones de nuestro trabajo que el linfoma de burkitt un tumor muy agresivo por su alta esta replicación y proliferación linfocitos vez que afecta principalmente a niños y adultos jóvenes es fundamental luego el diagnóstico iniciar rápido ciclos de quimioterapia ya que evolucionan muy rápidamente es fundamental también evitar el síndrome del issys tumoral y bueno lamentablemente estos linfomas tienen un muy mal pronóstico por lo cual la mayoría luego la mayoría pacientes lo va a ser diagnosticado se mueren lamentablemente bueno esta bibliografía consultada queremos agradecemos a nuestros compañeros de residencia que no escucharon par de veces al servicio de oncología

Traducion

As strange as the creatures of the microcosmos are, their lives still revolve around the same fundamentals that ours do. There’s food, there’s reproduction, and there’s death. Yes, even microbes, hardy as they can be, experience death. In some ways, you could say they invented it. And on our journey through the microcosmos, we’ve watched those deaths through many lenses. Some are slow, calm affairs, while others are explosive or creepy. And today, we’re going to try something new for our channel. We have gathered a few of our favorite episodes about death in the microcosmos so that we can see where our journey has taken us. So yeah, this is the kind of video you can turn on, and leave on for awhile.

This first video is also one of our oldest, so you’ll notice that a lot of footage in it looks very different from what we show these days because thanks to the support of our viewers, we’ve been able to upgrade our microscope multiple times over the course of this show. So the microscope may be different.

But the death, well, the death remains the same. This round little unicellular creature came to us via a plankton net, a mesh with tiny, microscopic holes through which we ran hundreds and hundreds of liters of water, letting us collect anything too large to pass through. We haven’t been able to identify this species yet, making it a bit of a mystery.

But the bigger mystery is still to come because this little creature is about to undergo that most universal and unknowable experience of all, death. Death comes to the microcosmos in many forms. Like this Stentor Polymorphous, slowly expelling the contents of its once trumpet-like body into the surrounding environment.

Or this dead larva, whose exoskeleton is now an inanimate host to two unicellular organisms. Even the mighty tardigrade, which has survived as a species through multiple mass extinctions, is not immune to death. This is, of course, the natural order of things. Predators hunt, and their prey attempts to survive, with varying levels of success.

This is Loxophyllum meleagris, a large unicellular organism that we’ve shown before eating a rotifer. This one is practically stuffed with those multicellular creatures, we counted five rotifers inside of it. But sometimes the predator becomes the prey, and even the Loxophyllum meleagris has to find ways to ensure its survival when other species come after it.

This seemingly unlikely threat is the Lacrymaria olor. Its name in Latin means “tears of a swan”, a name that suits both its teardrop shape and its neck-like extension, which gets up to eight times longer than its body in search of prey. Sometimes, we can see its neck poking out of the dirt on our microscope slide.

But even knowing that, you’d be forgiven for thinking it unlikely that something so small could pose a problem for those larger Loxophyllum. And yet, the Lacrymaria manages to take quite a chunk out of the Loxophyllum. The Loxophyllum though, survives thanks to its ability to regenerate the piece that was taken, but not all prey gets so lucky. Here, this rotifer has been killed by a heliozoan, destined to become food, a fate that this flagellate is about to share as it becomes captured by a heliozoan that is in the middle of cell division. The flagellate has been trapped by those long extensions, called axopods, that radiate out

from the heliozoan’s body. As the flagellate comes further in, it will be engulfed by the cells into its own food compartment called a vacuole. There, it will be lysed open and its contents digested by the heliozoa. In the end though, the natural order comes for predators too. Here, another heliozoan’s dying cellular body attracts the various

decomposers of the microbial world. Aside from predators, there are many other factors that lead a single-celled organism to die, changes in temperature, oxygen concentration, pH, water quality, so much more. This single-celled organism is swollen because the water surrounding it is entering the cell via osmosis. Many organisms have water pumps called contractile vacuoles that they use to push water back out and prevent that swelling. But as in the case of this organism, sometimes those contractile vacuoles stop working, and when that happens, the cell swells and explodes. Other times, the cause of death is harder to determine, like this Paradileptus that spent several hours swimming before going still, its shape beginning to change until it melts away, seeming to kill not only the Paradileptus but this small green cell swimming nearby, but leaving other smaller flagellates seemingly unaffected. And this brings us back to the beginning, with our mystery organism that is about to undergo a death laden with more mysteries. At first, the cell looks like it’s just melting away, dissolving into something that resembles a microbial Milky Way, except that for a few seconds, it almost looks like the cell membrane is able to close itself back up. We think, though we can’t know for sure, that some of the mechanisms inside the cell are still working, and that the organism is trying to recover. But alas, survival is not in the cards. Its membrane goes through lysis, releasing its insides into the surrounding environment. This death is unlike any other kind of death we’ve observed under our microscope, and we’re still not sure what caused it.

Perhaps there were so many organisms in the sample that they depleted the oxygen, and this organism could not continue cellular respiration. But perhaps it was something else. Death at every size holds its own mysteries, but it also reveals. The observations we make, even the guesses we come up with, tell us about the way these microbes interact with their environment, the way their own bodies work, and the connections that exist between them. It is only ever in the mysteries that knowledge is waiting to be found. So we just saw a small fraction of how many ways there are for microbes to die. But maybe now you’re asking yourself a more fundamental question: what even is death?

Well, weirdly, none of us will ever fully know the answer. But that doesn’t mean we can’t try to use what we know of chemistry and life to begin to describe it, as we’ll see in our next video. This is a ciliate, Loxodes magnus. It is about to die. Of course, depending on your time scale, we’re all about to die.

To the grand canyon, or the sun, things that have existed for millions or billions of years, we are each weird little bubbles of peculiar chemistry that form and then pop, form, and then pop. But this ciliate, and with our new microscope you can really see those cilia beating, is about to pop right before your eyes.

It looks fine right now. You can even see, inside it, it’s last meal, a Trachelomonas. So we don’t think it’s starving to death. It seems to be trucking along just fine. Loxodes Magnus are microaerophilic organisms, preferring a low concentration of dissolved oxygen in their environment, but not too low.

So maybe the concentration on the slide was too high, though we’ve witnessed many others who have been just fine in our preparations. So no, we can’t tell you why this ciliate is about to die, but we can tell you that right here, that’s where James, our master of microscopes, first saw something strange.

The moment the ciliate shifted direction, a little trail of cell membrane and cytoplasm. No reason. Nothing grabbed it, it didn’t snag on anything. But a little bit of what was once a part of the organism was suddenly, no longer a part of it. That cytoplasm is full of complicated molecules that are what chemists would call, far from equilibrium.

Equilibrium is the situation in which chemicals no longer have a tendency to react over time. In general, a thing that you can say for sure is that all the stuff outside of living cells is either at chemical equilibrium, or it is headed there. Whereas stuff inside cells is not at equilibrium, and it’s not headed there either.

How are all of these chemicals that, if left alone, would rapidly reach equilibrium managing to not do that? Life. That is what life is. A bunch of chemicals that take in energy in order to keep each other from reaching equilibrium. Quick break from our friend, the way we define life in biology classes is, wrong.

It’s not even really a definition, it’s a set of qualifying factors. Life has to take in energy. Life has to reproduce, it must respond to its environment, it must consist of cells. This is not a definition, it’s an attempt to draw a line, to create a boundary. And that makes sense for things that are actually amorphous and complicated, like social constructs.

But life is not a construct of our opinions, but of reality. Life is a chemical system that uses energy to keep itself from reaching chemical equilibrium. Why do they do it? Oh, well maybe let’s not go that deep, at least not today. Suffice it to say, a system that did this developed on this planet and now, billions of years later, it is still doing it. We have many things in common with this ciliate, and not to belabor the point, but one of those things is that we will die. You’ve may have noticed by now that this video isn’t about what life is, it’s about what death is. It’s just that, first, we had to define life.

Life is chemicals working together to take in energy to keep themselves far from equilibrium. Death is not the return to chemical equilibrium. The process of decay can last decades. Likewise, many parts of my body will return to equilibrium over the course of my life, I’m shedding skin cells right now and so are you.

The atoms and molecules of my body are replaced with new ones over and over and over again. But I will only die once. Likewise, our ciliate has been shedding cytoplasm and cell membrane for minutes now, and that shed cytoplasm is dead, no doubt. But the organism lives. Its chemistry continues. For now. Death is the moment when the system that maintains the far from equilibrium state ceases existence. And we can imagine that at many scales. That can happen to individual bits of an organism, as it is happening to the chemicals spilling out of our Loxodes right now. It can also happen to an individual cell in an organism.

And that happens all the time. It is happening right now inside you. It can also happen to an organism. That’s what we usually think of as death, with our focus, so often, on the individual. But we can keep moving up the scale and find yet other kinds of death. When a common genetic system that was useful for keeping many similar but individual organisms alive ceases to exist, that is an extinction. A kind of death. And when the system that has kept all life on earth far from equilibrium for billions of years, that system that we all share of nucleic and amino acids, when that ceases to exist, that will be something else. A terrible kind of death that we do not even have a name for. But it will be a death. The largest death, I suppose, until heat death, when everything in the universe has found equilibrium. Our ciliate is about out of time now. I don’t know when we can call it, when we can pronounce the time of death, but this seems as good a time as any. Here, we have death. The system that was using energy to keep itself from reaching equilibrium has ceased to exist.

Hey, welcome back. If you’ve come out of that video with some existential dread about the state of the universe, that is very reasonable. However, on our next stop in this journey, we’re going to argue that sure, chemical equilibria are scary, but if you’re a nematode, maybe you should worry about fungi first.

There are plenty of horror stories that begin innocuously enough. A new home, a camping trip with friends, a doll purchased at an estate sale…. This one starts with some ponds, the same set of ponds that James, our master of microscopes, has been sampling every week for the past three years. Which means that he’s collected so many microbes from these waters that you might think they’d get a bit boring or redundant. But you should never underestimate nature’s capacity for surprise. Recently, James came home with some samples from these ponds. And as usual, he prepared some slides and checked on the organisms within, finding some nematodes like this one slithering about on the slide.

And all seemed well, so he stored the slides and his new friends in a humidity chamber and waited to observe them after a few more days. But two days later, all would not be well. This is where we build our suspense. In a movie, this would be the moment where we assess the unsettling basement or the dark woods, and then consider retreating to safety. This is the creepy doll, only there hasn’t been any thumps in the middle of the night, so everything seems okay, right? We’re looking at the spores of a fungus, one belonging to the group Arthrobotrys. And when it’s just floating around like this, it seems quite harmless—especially when compared to the nematodes we showed earlier, which are part of a whole family of worms that are notorious for their parasitic lifestyle. And if you were to write off Arthrobotrys as a potential threat, you would be correct… most of the time. It does spend much of its life aligned with the dead, but only to sustain itself on the

remains of decayed life and organic matter. Arthrobotrys species are found all around the world, occupying everything from soil to animal feces in the many varied climates that make up our planet. And wherever it is, the fungus ensures that nutrients like nitrogen from dead organisms and other waste cycle through ecosystems.

But when nitrogen is scarce, these fungi will resort to hunting it down from living sources. And what better prey than the nematode, a fellow dweller of the soil and one of the most abundant animals on earth? When James put his slides into the humidity chamber, he had no notion of what these nematodes would be facing, and so no expectation of what he would find. But when the slides came back out, what he observed was something he’d only seen once before, in a drawing done two years ago by one of his close friends, Katelyn Solbakk. In it, you can see a nematode whose body has been clinched into segments by some kind of bulbous, thing.

What you’re seeing is the fungus’ most brutal design. But to get there, it must morph from decomposer to predator, no longer consuming what has already been dead, but actively killing. It begins by weaving a trap out of itself. It threads the hyphae of its mycelium out and then back in, forming a living loop that repeats to form a net. But a net is only one part of a trap, the other part is the lure. The fungi can find nematodes by following traces of their pheromones like they’re breadcrumbs. And more nefariously, they can mimic the smell of certain food cues to draw the worm in, like a siren working through scent instead of song.

The nematode has no reason to suspect anything, even as it swims closer and closer and eventually through the fungal rings. But as it does, the movement of worm and water triggers the rings to constrict. The worm is trapped, but the worst is still yet to come. The fungus’ hyphae begin to grow off from the loop, puncturing the worm’s cuticle and paralyzing it.

The threads swell up into a bulb that produces more hyphae to spread through the rest of the nematode. And then the fungus feeds and feeds, quickly digesting the rest of the nematode’s body from within. It is a gruesome death. Here is one nematode, just recently trapped. And here is the worm again, four days later.

You can see the infection bulb where the fungus first punctured and expanded. And the whole body of the worm seems taken over, no longer a clear tube, but instead a corpse that has become home to its cause of death. The Arthrobotrys fungi are not the only ones capable of trapping and feeding upon nematodes.

There is a whole range of nematode-trapping fungi with their own methods, though the species Arthrobotrys oligospora is perhaps the most plentiful of these fungi and also the best studied. Maybe it’s just us, but it’s somewhat unsettling to realize that this insidiousness is all the work of a fungus, a thing that can seem so inert compared to the wiggling, active worm that it targets. But fungi do have a kinship with horror stories. Their frequent role as decomposers naturally connects them with the dead. Plus, they come equipped with their own creeping sense of dread with images of mycelia weaving through bodies. And authors have drawn inspiration from the notion of fungal horror.

There are many works–like the famous Gothic tale We Have Always Lived in the Castle, or the short story “The Voice in the Night,” or recent novels like Mexican Gothic and Wanderers— that draw on everything from poisonous mushrooms to colonizing fungi to create their terror. But whatever we seek to scare ourselves with in fiction, horror has its purpose in nature.

As we’ve pointed out, nematodes are one of the most abundant animals on earth. They play an important role in decomposition…but they’re also the source of many diseases—both in animal bodies and in plants. So having them be slightly less abundant is important to our ecosystem as well. In fact, scientists have been studying these fungi to develop better nematode-fighting

strategies for agriculture. So as is the case with many good horror villains, there is a version of this story where the nematode-trapping fungus is the hero. Unless, of course, you’re the nematode. And for our last video, our microbes are dying at the hands of an unusual enemy. It’s James, with an UV laser, in the laboratory. Maybe it sounds like a microscopic version of the game Clue, but there’s a point to it all, we swear. Blepharisma have appeared on our channel several times before. In fact, this channel got its start thanks to a video that James, our master of microscopes, once posted of a Blepharisma dying. Around three million people watched that video, including me, your host Hank Green.

So if you enjoy this channel, you can thank that dead Blepharisma. But perhaps you should wait for another day to thank them. Because in about ten seconds, you’re going to watch a Blepharisma explode. Here it is, glowing with autofluorescence underneath UV light. You can see its oblong shape and oral groove outlined in red…but not for long.

The red becomes brighter and brighter, but it also looks like it’s starting to expand. And then suddenly, the walls of the blepharisma burst, the organism popping like a crimson balloon. The blepharisma bubbles and pours into its surroundings and it all happens within a matter of seconds. Let’s watch it again.

Dead or dying microbes are a common enough sight in our journey through the microcosmos. And there are many potential culprits behind these deaths: predators, accidents, environmental changes, the inevitable march of life into death. But the culprit this time… well, it was us. Us and the UV light that is part of our new fluorescence microscope upgrade.

And our UV light has been very exciting for us. In particular, it’s allowed us to look for methanogens, or Archaea, which sometimes take up residence inside protists. Under normal light, it’s hard to tell the tiny archaea and the tiny bacteria apart. But under UV light, the archaea will shine blue. So UV can reveal new aspects of the microcosmos.

But if you’ve ever fallen asleep on a beach or just stayed out in the sun a bit too long, you may have also experienced the darker side of UV light. No one wants a sunburn, but fortunately, we have defenses, like hair, and melanin, and sunscreen which can block or absorb UV rays before they cause further damage in our cells.

We also, and this is crucial, have more than one cell…so if some of them die, which when you get a sunburn they do, the rest of our bodies can live on. Not all organisms have these sorts of protections. Or if they do, they’re designed for exposure to the sun, not the intense scrutiny of our UV light.

So when James wants to hunt Archaea, he has to be careful. He can quickly shine the UV light to see if anything blue appears. But he has to quickly shut it off. Because as we’ve seen, even a few seconds of exposure to the UV light will kill off his pond buddies. We want to note that as we said earlier, death is a common reality of the microcosmos…we

just usually prefer to walk in on a microbe dying rather than being the cause of death. But for this episode, we decided to make an exception and use our UV light for an extended period of time, with the knowledge that it would kill the microbe we were watching. Because these explosions illustrate the cost of doing business with light.

The word for this business is phototoxicity. Death by light. And while it can happen under other monochromatic lights, the particular wavelength and intensity of our UV light makes it much more harmful to our organisms than our other red, blue, or green light sources. This death starts with excitation.

When the light hits the organism, it can potentially excite chemical structures inside the cell, sending electrons up and down, and producing fluorescent colors in the process. But the colors aren’t the only thing that gets created. If there’s oxygen around, it will react with the excited fluorescent molecule, creating what are known as reactive oxygen species. In biology, reactive oxygen species are byproducts of different cellular processes that metabolize oxygen, which can make them part of normal life. There are even reactive oxygen species that are involved in signaling pathways. But the “reactive” in their name is key to what makes an excess amount of them dangerous.

If you are an organism, and you are, there are a lot of reactions you want to have happen in your cells. You want your DNA to link together correctly, you want your enzymes to find the right substrates. But reactive oxygen species are happy to react with all of those molecules too, damaging them and getting in the way of the chemistry that we need to survive.

What phototoxicity will look like depends on the organism and the light being directed at it. For the organisms we’ve been showing here, like this homalozoon, the overall effect of this intense UV light seems to be unanimous: the cell swells up and bursts open, like a galaxy erupting on our slide. But while the overall effect is the same, the internal machinations are likely different, triggered by a complex interplay of different chemicals that nonetheless react to our light source in a similar, catastrophic fashion. While we’re not sure of the culprits behind the homalozoon’s death, we can identify one of the chemicals that likely sets off the blepharisma’s death. It’s the reddish pigment molecule called blepharismin that gives the ciliate its color under more normal circumstances. Outside of the UV light, you can see the membrane-bound pigments neatly distributed along the rows that stretch from one end of the blepharisma to the other. But under our UV light and with oxygen in the environment, the blepharismin reacts to form reactive oxygen species, and death follows quickly from there.

But while toxic in our experiment, we should note that the blepharismin serves a key purpose for the blepharisma: defense. These pigment molecules are toxic to some of Blepharisma’s predators in both the light and the dark. That makes the pigment somewhat like UV light: necessary for survival, yet also a delicate negotiation.

But in the same way that we manage our relationship with the sun, scientists have learned ways to manage these phototoxic reactions. They’ve had to in order to understand how we can use fluorescence microscopy to study cells and organisms. They’ve learned how to modulate wavelength and intensity and duration, along with many other factors, to wield light in a way that better serves their purposes. In the case of the blepharisma, for example, scientists found that using a moderate light for around 1 hour wasn’t much of a problem for them. But with more time under the light, the cells would eventually die. It’s easy to think of the microcosmos as a separate world from us, even when we know that the microscope is a bridge between large and small. But these deaths at the hand of our supposed bridge are a cautionary sign that we are encountering microbes in a world that is both natural and manufactured at the same time. The way that we light that world impacts the way we see the organisms, and it also shapes their lives—reminding us that they are stronger often than we can fathom, but fragile nonetheless. And that brings us to the end of our tour of death in the microcosmos today, an end to a story of ends, you might say. But maybe what we’ve seen today is that there really is no end, is there? Just pauses on individual stories that nonetheless endure in the remains of the world left behind.

Thank you for coming on this journey with us as we explore the unseen world that surrounds us. And thank you to all of our patrons who make videos like the ones we’ve watched today possible. This channel could not exist without your support and we are so thankful for it. If you’d like to join the list of patrons you’re currently seeing on your screen, you can go to patreon.com/journeytomicro. And if you’d like to see more from our Master of Microscopes, James, you can check out Jam & Germs on Instagram, and if you’d like to see more from us, there’s probably a subscribe button somewhere nearby.

Shutterstock

Shutterstock